U of I helps explore strange new worlds

|

|

October 24, 2013 |

|

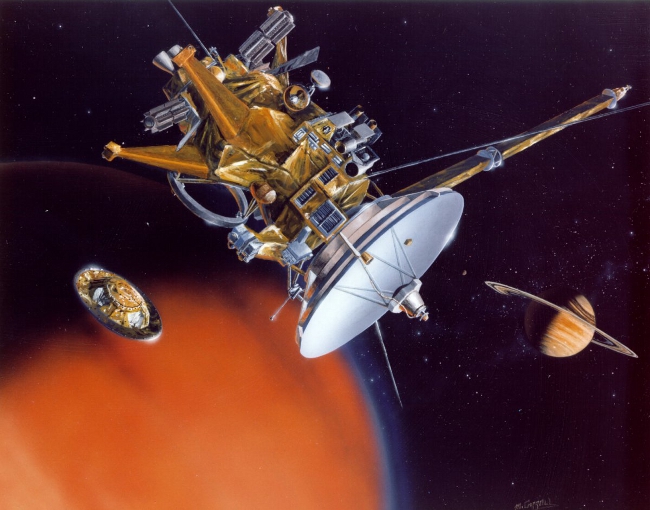

| The

bus-sized Cassini spacecraft releases

the European Space Agency’s Huygens

probe over hazy Titan. Image: NASA. |

|

A team of NASA researchers around the nation,

including scientists at the University of Idaho,

revealed today a new view of Saturn’s moon

Titan.

With the sun now shining down over Titan, a

little luck with the weather, and trajectories

that put the spacecraft into optimal viewing

positions, NASA's Cassini spacecraft has

obtained new pictures of the liquid methane and

ethane seas and lakes that reside near Titan's

north pole. The images reveal new clues about

how the lakes formed and Titan's Earth-like

"hydrologic" cycle that involves hydrocarbons

rather than water.

"The view from Cassini's visual and infrared

mapping spectrometer gives us a holistic view of

an area that we'd only seen in bits and pieces

before and at a lower resolution," said Jason

Barnes, an associate professor in the UI

Department of Physics who is part of NASA’s

Cassini visual and Infrared mapping

spectrometer, or VIMS, team. "It turns out that

Titan's north pole is even more interesting than

we thought, with a complex interplay of liquids

in lakes and seas and deposits left from the

evaporation of past lakes and seas."

Both Barnes and Matt Hedman, an assistant

professor of physics at UI, work on the Cassini

project as participating scientists in the VIMS

team, which has recently released a number of

images including a spectacular view of Saturn

and its rings backlit by the sun.

Three doctoral students working under Barnes –

Graham Vixie, Casey Cook, and Shannon MacKenzie

– also work on the project, as well as

undergraduate student Corbin Hennen.

While there is one large lake and a few smaller

ones near Titan's south pole, almost all of

Titan's lakes appear near the moon's north pole.

Cassini scientists have been able to study much

of the terrain with radar, which can penetrate

beneath Titan's clouds and thick haze. And

Cassini's VIMS and imaging science subsystem

have only been able to capture distant, oblique

or partial views of this area until now.

Several factors combined recently to give these

instruments great observing opportunities. Two

recent flybys provided better viewing geometry.

Sunlight has begun to pierce the winter darkness

that shrouded Titan's north pole at Cassini's

arrival in the Saturn system nine years ago. A

thick cap of haze that once hung over the north

pole has also dissipated as northern summer

approaches. And, thankfully, Titan's beautiful,

almost cloudless, rain-free weather continued

during Cassini's flybys this past summer.

The image from VIMS is a mosaic in infrared

light based on data obtained during a flyby of

Titan on Sept. 12, 2013. The colorized mosaic,

which maps infrared colors onto the

visible-color spectrum, reveals differences in

the composition in material around the lakes.

The data suggest parts of Titan's lakes and seas

may have evaporated and left behind the Titan

equivalent of Earth's salt flats. Only here, the

evaporated material is thought to be organic

chemicals originally from Titan's haze particles

that once dissolved in liquid methane. They

appear orange in this image against the greenish

backdrop of Titan's typical bedrock of water

ice.

Launched in 1997, Cassini has been exploring the

Saturn system since 2004. A full Saturn year is

30 years and Cassini has been able to observe

nearly a third of a Saturn year. In that time,

Saturn and its moons have seen the seasons

change from northern winter to northern summer.

"Titan's northern lakes region is one of the

most Earth-like and intriguing in the solar

system," said Linda Spilker, the Cassini project

scientist based at NASA's Jet Propulsion

Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "We know lakes

here change with the seasons and Cassini's long

mission at Saturn gives us the opportunity to

watch the seasons change at Titan, too. Now that

the sun is shining in the north and we have

these wonderful views, we can begin to compare

the different data sets and tease out what

Titan's lakes are doing near the north pole."

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative

project of NASA, the European Space Agency and

the Italian Space Agency. JPL manages the

mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate,

Washington. The California Institute of

Technology in Pasadena manages JPL for NASA. The

VIMS team is based at the University of Arizona

in Tucson. The imaging operations center is

based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder,

Colorado.

For more information about the Cassini mission,

visit:

www.nasa.gov/cassini and

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov. |

|

Questions or comments about this

article?

Click here to e-mail! |

|

|

|

|